Example Applications

Carbon dioxide sequestration

dfnWorks provides the framework necessary to perform multiphase simulations (such as flow and reactive transport) at the reservoir scale. A particular application, highlighted here, is sequestering CO2 from anthropogenic sources and disposing it in geological formations such as deep saline aquifers and abandoned oil fields. Geological CO2 sequestration is one of the principal methods under consideration to reduce carbon footprint in the atmosphere due to fossil fuels (Bachu, 2002; Pacala and Socolow, 2004). For safe and sustainable long-term storage of CO2 and to prevent leaks through existing faults and fractured rock (along with the ones created during the injection process), understanding the complex physical and chemical interactions between CO2 , water (or brine) and fractured rock, is vital. dfnWorks capability to study multiphase flow in a DFN can be used to study potential CO2 migration through cap-rock, a potential risk associated with proposed subsurface storage of CO2 in saline aquifers or depleted reservoirs. Moreover, using the reactive transport capabilities of PFLOTRAN coupled with cell-based transmissivity of the DFN allows one to study dynamically changing permeability fields with mineral precipitation and dissolution due to CO2 –water interaction with rock.

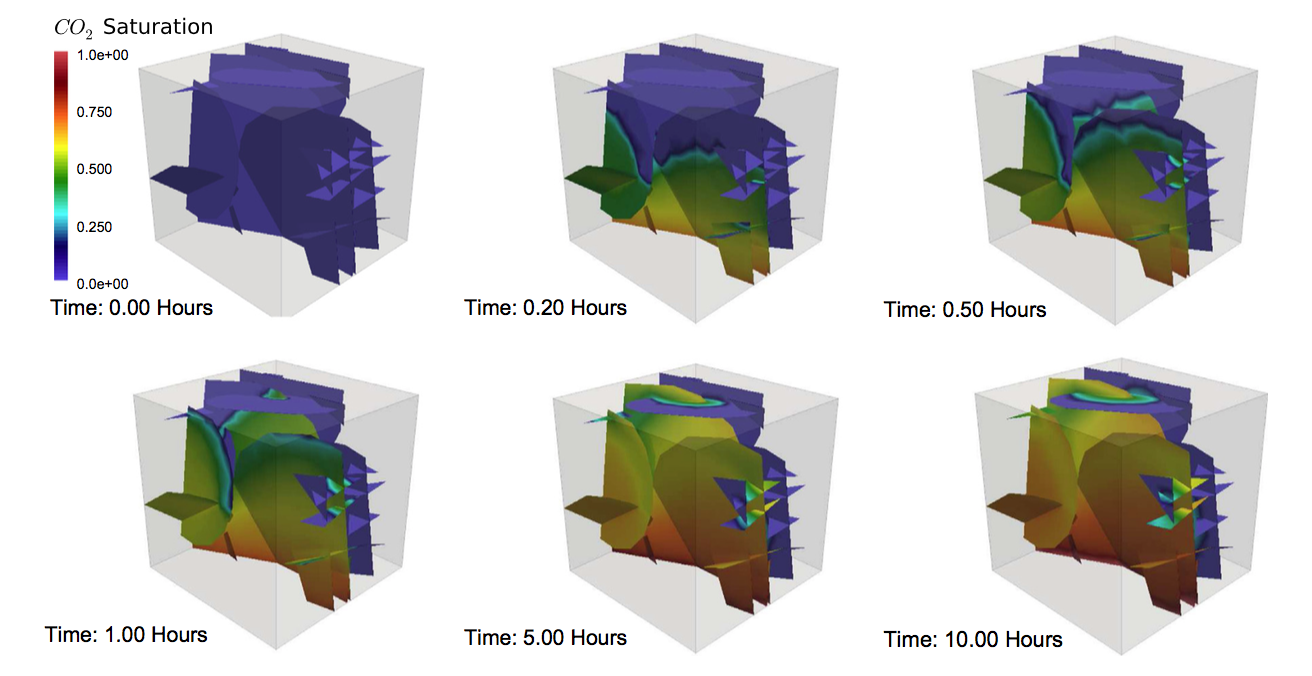

Temporal evolution of supercritical |CO2| displacing water in a meter cube DFN containing 24 fractures. The DFN is initially fully saturated with water, (top left time 0 hours) and supercritical |CO2| is slowly injected into the system from the bottom of the domain to displace the water for a total time of 10 h. There is an initial flush through the system during the first hour of the simulation, and then the rate of displacement decreases.

Shale energy extraction

Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has provided access to hydrocarbon trapped in low-permeability media, such as tight shales. The process involves injecting water at high pressures to reactivate existing fractures and also create new fractures to increase permeability of the shale allowing hydrocarbons to be extracted. However, the fundamental physics of why fracking works and its long term ramifications are not well understood. Karra et al. (2015) used dfnWorks to generate a typical production site and simulate production. Using this physics based model, they found good agreement with production field data and determined what physical mechanisms control the decline in the production curve.

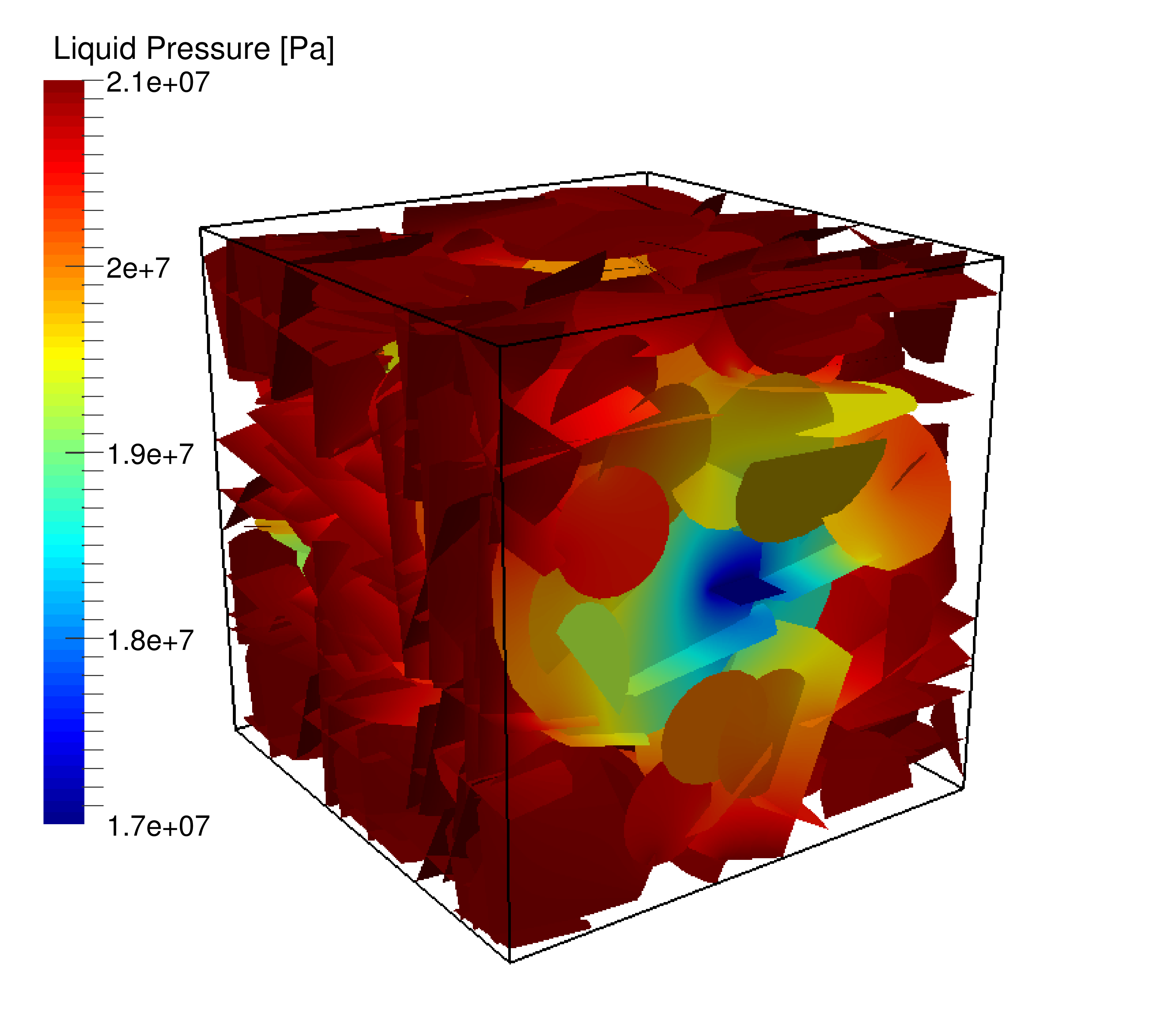

Pressure in a well used for hydraulic fracturing.

Nuclear waste repository

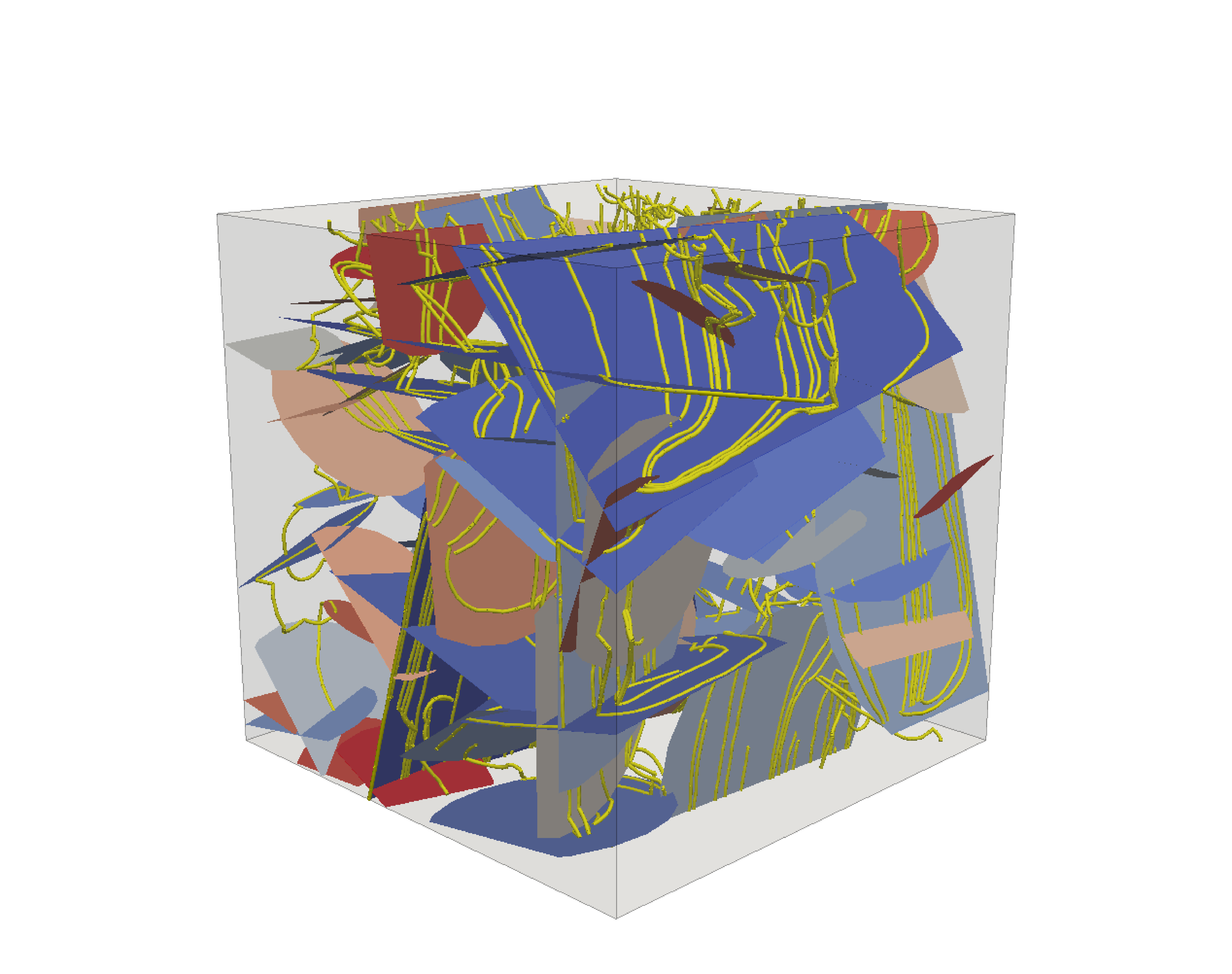

The Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (SKB) has undertaken a detailed investigation of the fractured granite at the Forsmark, Sweden site as a potential host formation for a subsurface repository for spent nuclear fuel (SKB, 2011; Hartley and Joyce, 2013). The Forsmark area is about 120 km north of Stockholm in northern Uppland, and the repository is proposed to be constructed in crystalline bedrock at a depth of approximately 500 m. Based on the SKB site investigation, a statistical fracture model with multiple fracture sets was developed; detailed parameters of the Forsmark site model are in SKB (2011). We adopt a subset of the model that consist of three sets of background (non-deterministic) circular fractures whose orientations follow a Fisher distribution, fracture radii are sampled from a truncated power-law distribution, the transmissivity of the fractures is estimated using a power-law model based on the fracture radius, and the fracture aperture is related to the fracture size using the cubic law (Adler et al., 2012). Under such a formulation, the fracture apertures are uniform on each fracture, but vary among fractures. The network is generated in a cubic domain with sides of length one-kilometer. Dirichlet boundary conditions are imposed on the top (1 MPa) and bottom (2 MPa) of the domain to create a pressure gradient aligned with the vertical axis, and noflow boundary conditions are enforced along lateral boundaries.

Simulated particle trajectories in fractured granite at Forsmark, Sweden.

Sources:

Adler, P.M., Thovert, J.-F., Mourzenko, V.V., 2012. Fractured Porous Media. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Bachu, S., 2002. Sequestration of CO2 in geological media in response to climate change: road map for site selection using the transform of the geological space into the CO2 phase space. Energy Convers. Manag. 43, 87–102.

Hartley, L., Joyce, S., 2013. Approaches and algorithms for groundwater flow modeling in support of site investigations and safety assessment of the Fors- mark site, Sweden. J. Hydrol. 500, 200–216.

Karra, S., Makedonska, N., Viswanathan, H., Painter, S., Hyman, J., 2015. Effect of advective flow in fractures and matrix diffusion on natural gas production. Water Resour. Res., under review.

Pacala, S., Socolow, R., 2004. Stabilization wedges: solving the climate problem for the next 50 years with current technologies. Science 305, 968–972.

SKB, Long-Term Safety for the Final Repository for Spent Nuclear Fuel at Forsmark. Main Report of the SR-Site Project. Technical Report SKB TR-11-01, Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co., Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.